The War of Independence: Since the 18th century, according to best-medical-schools, a new class of Greek merchants and long-distance traders, thanks to their contacts with Central and Western Europe, have also acted as mediators of the ideas of the Enlightenment and of national ideas and movements. From their ranks the founders of the revolutionary secret society of Philiki Hetairia (went Hetaeria) indicates who took over the organizational preparation of the Greek revolt against Turkish rule. Under the impression of the successful Serbian uprisings (1804-17), the dispute between the Sultan and the insubordinate Ali Tepedelenli, Pasha of Jannina, and in reliance on Russian help, A. Ypsilanti moved with his saints on March 6, 1821 in the Danube Principality of Moldova and called for an uprising. However, there was no Russian support and after the defeat of Dr ǎ g ǎ șani on June 19, 1821, the company failed. On March 25, 1821, the uprising began in Greece proper, which was initiated by the call of Archbishop Germanos of Patras (* 1771, † 1826) got a strong boost to the war of liberation. In the first attempt, the Greeks succeeded, with the exception of a few cities (Tripoli, Nauplia), the Peloponnese and, on May 7, 1821, also to bring Athens into their hands. Different objectives and personal animosities between the spokesmen for the uprising and the military commanders, tangible local special interests and the rivalries of competing family clans hindered the political implementation of the initial successes. The short-term alliance between the Klephtenführer T. Kolokotronis and the lord of the Mani Peninsula Petros Mavromichalis (* 1765, † 1848; “Petrobey”) was not enough to enable a joint government to be formed and to contain the spreading internal power struggles, which very quickly reached a level similar to that of a civil war. On 1./13. 1. In 1822 a national assembly meeting in Epidaurus proclaimed the independence of Greece; On January 27, 1822, the “Organic Law of Epidaurus”, based on Western European models, was adopted.

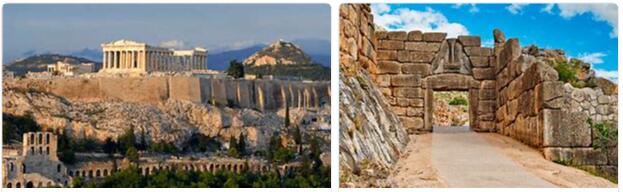

The Turkish reaction began with the execution of the Partriarch Gregorios V on April 22, 1821. After the submission of the Pasha of Jannina, troops advanced against the Greek insurgents. These were initially able to repel the Turkish armed forces; Attempts to extend the survey to Epirus, however, failed. The Greek uprising met with a wide response. About a thousand volunteers – among them the English poet Lord Byron - moved to Hellas, money and donations in kind were raised (Philhellenes); at the same time, however, the rebels wore themselves out in two civil wars in 1823/24 over the internal order of the liberated area. In February 1825, the Turkish governor of Egypt, Mehmed Ali, sent, his son Ibrahim Pasha with a well-trained army and a strong fleet to the Peloponnese. By the end of the year he had subdued the entire peninsula, apart from the mountainous areas that were difficult to access. On April 22nd, 1826, Missolunghi (Mesolongion) fell after a siege of almost a year, and on August 15th, 1826 also Athens, where only the occupation of the Acropolis (until June 1827) could hold out. In view of further Turkish-Egyptian successes, the Greek Klephten leaders elected Count I. A. Kapodistrias as regent on April 11, 1827 for seven years.

On July 6, 1827, Russia, Great Britain and France agreed in the London Treaty on armed intervention in the Turkish-Greek war. The combined fleets of the three powers destroyed the Turkish-Egyptian naval forces at Navarino on October 20, 1827 without a declaration of war. A French expeditionary force intervened in the Peloponnese, and Tsar Nicholas I. declared war on Turkey on April 26, 1828. The Greeks used the sultan’s military ties to regain a foothold north of the Gulf of Corinth in May 1829. Great Britain, under the influence of the Russo-Turkish Peace of Adrianople (September 14, 1829), obtained full sovereignty of a Kingdom of Greece in the London Protocol of February 3, 1830. Its territory consisted of southern and central Greece, including Euboea and the Cyclades, but excluding Crete, the Ionian Islands and most of Thessaly and the archipelago, based on today’s national territory. The intended king, Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, withdrew the promise he had already given (since 1831 as Leopold I, King of the Belgians). Kapodistrias who strictly wanted to eliminate the anarchic conditions in the war-ravaged country, was murdered on October 9, 1831. His brother Augustinos Graf Kapodistrias (* 1778, † 1857) succeeded him as (provisional) regent. In the London Treaty of May 7, 1832, the great powers agreed on the as yet underage Prince Otto of Bavaria as pretender to the throne.

Otto’s government: On August 8, 1832, the Greek National Assembly approved Otto’s accession to the throne (February 6, 1833). Until Otto came of age (1835), a Regency Council under J. L. Graf von Armansperg ruled the new state. A loan from the great powers and a Bavarian protection force of 3,500 men were supposed to give stability to the regime. The preference for non-Greek personalities in government and administration and the lack of adaptation to the Greek way of thinking cost the “Bavarocracy” a great deal of sympathy. The political support of Armansperg in Great Britain aroused distrust in Paris and Saint Petersburg. On December 20, 1837, the first “national” cabinet was constituted. Diplomatic relations with the Ottoman Empire were established in 1839, but were already burdened by a revolt of the Greek residents in Crete in 1841. The internal political unrest was expressed on September 15, 1843 in a bloodless uprising by the Athens garrison, as a result of which the majority of foreigners were dismissed from the Greek civil service and a constitution was promulgated by a constituent national assembly on March 18, 1844, and by King Otto was sworn in.

The foreign policy model of the Greeks in the 19th century was the “Megal Idea”, the “Great Idea” of the re-establishment of a Greater Greek Empire based on the Byzantine model with the capital Constantinople. The Crimean War (1853 / 54–56) seemed to make a first step towards this possible, but military successes of the Greeks in Epirus were nullified by an Anglo-French occupation of Piraeus. The dissatisfaction of leading circles with the foreign policy unsuccessful king led to a rebellion in February 1862 and on October 23, 1862 to the removal of the king by a provisional government. The royal couple left Piraeus on an English ship without a formal abdication.